Icon

An icon (from Greek εἰκών eikōn "image") is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, from Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism. More broadly the term is used in a wide number of contexts for an image, picture, or representation; it is a sign or likeness that stands for an object by signifying or representing it either concretely or by analogy, as in semiotics; by extension, icon is also used, particularly in modern culture, in the general sense of symbol — i.e. a name, face, picture, edifice or even a person readily recognized as having some well-known significance or embodying certain qualities: one thing, an image or depiction, that represents something else of greater significance through literal or figurative meaning, usually associated with religious, cultural, political, or economic standing.

Throughout history, various religious cultures[1] have been inspired or supplemented by concrete images, whether in two dimensions or three. The degree to which images are used or permitted, and their functions — whether they are for instruction or inspiration, treated as sacred objects of veneration or worship, or simply applied as ornament — depend upon the tenets of a given religion in a given place and time.

In Eastern Christianity and other icon-painting Christian traditions, the icon is generally a flat panel painting depicting a holy being or object such as Jesus, Mary, saints, angels, or the cross. Icons may also be cast in metal, carved in stone, embroidered on cloth, painted on wood, done in mosaic or fresco work, printed on paper or metal, etc. Creating free-standing, three-dimensional sculptures of holy figures was resisted by Christians for many centuries, out of the belief that daimones inhabited pagan sculptures, and also to make a clear distinction between Christian and pagan art. To this day, in obedience to the commandment not to make "graven images", Orthodox icons may never be more than three-quarter bas relief. Comparable images from Western Christianity are generally not described as "icons", although "iconic" may be used to describe a static style of devotional image.

Christianity

Christianity originated as a movement within Judaism, a religion that traditionally did not tolerate figurative religious art, although at this period that prohibition seems to have been relaxed, as can be seen in the 3rd century paintings in the Dura-Europos Synagogue. There is evidence of the use of painted icons or of similar religious images by Christians in the New Testament or early apocrypha. Dr. Steven Bingham writes,[2] "The first thing to note is that there is a total silence about Christian and non-idolatrous images. It is important to note that the silence is in the New Testament texts, and this silence should not be interpreted as describing all the activities of the Apostles or 1st century Christians. The Gospel of John states that 'Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book...' (Jn 20.30). We could easily add that the Apostles also did and said many things not recorded in the New Testament. It is obvious, therefore, that we do not have a complete account of the activities and sayings of the Apostles. So, if we want to find out if the first Christians made or ordered any kind of figurative art, the New Testament is of no use whatsoever. The silence is a fact, but the reason given for the silence varies from exegete to exegete depending on his assumptions." In other words, relying only upon the New Testament as evidence of no painted icons amounts to an argument from silence. In addition, it should also be noted that Christian symbolic art and iconography had already developed extensively before the New Testament Canon was finalized in the 4th century.

Though the word eikon is found in the New Testament (see below), it is never in the context of painted icons though it is used to mean portrait. There were, of course, Christian paintings and art in the early catacomb churches. Many can still be viewed today, such as those in the catacomb churches of Domitilla and San Callisto in Rome.

In Eastern Orthodoxy and other icon-painting Christian traditions, the icon is generally a flat panel (generally of wood) painting depicting a holy being or object such as Jesus, Mary, saints, angels, or the cross. Icons may also be cast in metal, carved in stone, embroidered on cloth, done in mosaic work, printed on paper or metal, etc.

The earliest written records of Christian images treated like icons in a pagan or Gnostic context are offered by the fourth-century Christian Aelius Lampridius in the Life of Alexander Severus (xxix) that was part of the Augustan History. According to Lampridius, the emperor Alexander Severus (222–235), who was not a Christian, had kept a domestic chapel for the veneration of images of deified emperors, of portraits of his ancestors, and of Christ, Apollonius, Orpheus and Abraham. Irenaeus, (c. 130–202) in his Against Heresies (1:25;6) says scornfully of the Gnostic Carpocratians, "They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them. They crown these images, and set them up along with the images of the philosophers of the world that is to say, with the images of Pythagoras, and Plato, and Aristotle, and the rest. They have also other modes of honouring these images, after the same manner of the Gentiles [pagans]." St. Irenaeus on the other hand does not speak critical of icons or portraits in a general sense, only of certain gnostic sectarians use of icons.

Another criticism of image veneration is found in the non-canonical second-century Acts of John (generally considered a gnostic work), in which the Apostle John discovers that one of his followers has had a portrait made of him, and is venerating it: (27) "...he [John] went into the bedchamber, and saw the portrait of an old man crowned with garlands, and lamps and altars set before it. And he called him and said: Lycomedes, what do you mean by this matter of the portrait? Can it be one of thy gods that is painted here? For I see that you are still living in heathen fashion." Later in the passage John says, "But this that you have now done is childish and imperfect: you have drawn a dead likeness of the dead."

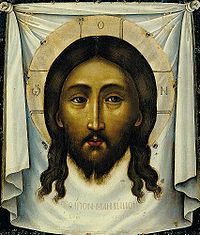

Aside from the legend that Pilate had made an image of Christ, the fourth-century Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Church History, provides a more substantial reference to a "first" icon of Jesus. He relates that King Abgar of Edessa sent a letter to Jesus at Jerusalem, asking Jesus to come and heal him of an illness. In this version there is no image. Then, in the later account found in the Syriac Doctrine of Addai, a painted image of Jesus is mentioned in the story; and even later, in the account given by Evagrius, the painted image is transformed into an image that miraculously appeared on a towel when Christ pressed the cloth to his wet face.[3] Further legends relate that the cloth remained in Edessa until the 10th century, when it was taken to Constantinople. In 1204 it was lost when Constantinople was sacked by Crusaders, but its iconic type had been well fixed in numerous copies.

Elsewhere in his Church History, Eusebius reports seeing what he took to be portraits of Jesus, Peter and Paul, and also mentions a bronze statue at Banias / Paneas, of which he wrote, "They say that this statue is an image of Jesus" (H.E. 7:18); further, he relates that locals thought the image to be a memorial of the healing of the woman with an issue of blood by Jesus (Luke 8:43-48), because it depicted a standing man wearing a double cloak and with arm outstretched, and a woman kneeling before him with arms reaching out as if in supplication. John Francis Wilson[4] thinks it possible to have been a pagan bronze statue whose true identity had been forgotten; some have thought it to be Aesculapius, the God of healing, but the description of the standing figure and the woman kneeling in supplication is precisely that found on coins depicting the bearded emperor Hadrian reaching out to a female figure symbolizing a province kneeling before him.

After Christianity was legalized by the emperor Constantine within the Roman Empire in 313, huge numbers of pagans became converts. This created the necessity for the transfer of allegiance and practice from the old gods and heroes to the new religion, and for the gradual adaptation of the old system of image making and veneration to a Christian context, in the process of Christianization. Robin Lane Fox states[5] "By the early fifth century, we know of the ownership of private icons of saints; by c. 480-500, we can be sure that the inside of a saint's shrine would be adorned with images and votive portraits, a practice which had probably begun earlier".

When Constantine converted to Christianity the majority of his subjects were still pagans and the Roman Imperial cult of the divinity of the emperor, expressed through the traditional burning of candles and the offering of incense to the emperor’s image, was tolerated for a period because it would have been politically dangerous to attempt to suppress it. Indeed, in the 5th century the portrait of the reigning emperor was still honoured this way in the courts of justice and municipal buildings of the empire and in 425 the Arian Philostorgius charged the orthodox in Constantinople with idolatry because they still honored the image of the emperor Constantine the Great, the founder of the city, in this way. Dix notes that this was more than a century before we find the first reference to a similar honouring of the image of Christ or his saints, but that it would seem a natural progression for the image of Christ, the King of heaven and earth, to be eventually paid the same cultic veneration as that given to the earthly Roman emperor.[6]

Constantine to Justinian

After adoption of Christianity as the only permissible Roman state religion under Theodosius I, Christian art began to change not only in quality and sophistication, but also in nature. This was in no small part due to Christians being free for the first time to express their faith openly without persecution from the state, in addition to the faith spreading to the non-poor segments of society. Paintings of martyrs and their feats began to appear, and early writers commented on their lifelike effect, one of the elements a few Christian writers criticized in pagan art — the ability to imitate life. The writers mostly criticized pagan works of art for pointing to false gods, thus encouraging idolatry. Statues in the round were avoided as being too close to the principal artistic focus of pagan cult practices, as they have continued to be (with some small-scale exceptions) throughout the history of Eastern Christianity.

Nilus of Sinai, in his Letter to Heliodorus Silentiarius, records a miracle in which St. Plato of Ankyra appeared to a Christian in a dream. The Saint was recognized because the young man had often seen his portrait. This recognition of a religious apparition from likeness to an image was also a characteristic of pagan pious accounts of appearances of gods to humans, and was a regular topos in hagiography. One critical recipient of a vision from Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki apparently specified that the saint resembled the "more ancient" images of him - presumably the 7th century mosaics still in Hagios Demetrios. Another, an African bishop, had been rescued from Arab slavery by a young soldier called Demetrios, who told him to go to his house in Thessaloniki. Having discovered that most young soldiers in the city seemed to be called Demetrios, he gave up and went to the largest church in the city, to find his rescuer on the wall.[7]

During this period the church began to discourage all non-religious human images - the Emperor and donor figures counting as religious. This became largely effective, so that most of the population would only ever see religious images and those of the ruling class. The word icon referred to any and all images, not just religious ones, but there was barely a need for a separate word for these.

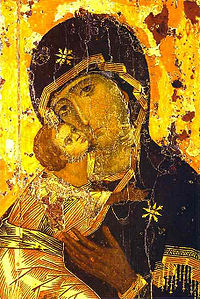

Luke's portrait of Mary

It is in a context attributed to the 5th century that the first mention of an image of Mary painted from life appears, though earlier paintings on cave walls bear resemblance to modern icons of Mary. Theodorus Lector, in his sixth-century History of the Church 1:1[8] stated that Eudokia (wife of Theodosius II, died 460) sent an image of "the Mother of God" named Icon of the Hodegetria from Jerusalem to Pulcheria, daughter of the Emperor Arcadius: the image was specified to have been "painted by the Apostle Luke." Margherita Guarducci relates a tradition that the original icon of Mary attributed to Luke, sent by Eudokia to Pulcheria from Palestine, was a large circular icon only of her head. When the icon arrived in Constantinople it was fitted in as the head into a very large rectangular icon of her holding the Christ child and it is this composite icon that became the one historically known as the Hodegetria. She further states another tradition that when the last Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin II, was leaving Constantinople in 1261 he took this original circular portion of the icon with him. This remained in the possession of the Angevin dynasty who had it likewise inserted into a much larger image of Mary and the Christ child, which is presently enshrined above the high altar of the Benedictine Abbey church of Montevergine.[9][10] Unfortunately this icon has been over the subsequent centuries subjected to repeated repainting, so that it is difficult to determine what the original image of Mary’s face would have looked like. However, Guarducci also states that in 1950 an ancient image of Mary[11] at the Church of Santa Francesca Romana was determined to be a very exact, but reverse mirror image of the original circular icon that was made in the 5th century and brought to Rome, where it has remained until the present.[12] In later tradition the number of icons of Mary attributed to Luke would greatly multiply;[13] the Salus Populi Romani, the Theotokos of Vladimir, the Theotokos Iverskaya of Mount Athos, the Theotokos of Tikhvin, the Theotokos of Smolensk and the Black Madonna of Częstochowa are examples, and another is in the cathedral on St Thomas Mount, which is believed to be one of the seven painted by St.Luke the Evangelist and brought to India by St. Thomas.[14] Ethiopia has at least seven more.[15]

Acheiropoieta

The tradition of acheiropoieta (αχειροποίητα, literally "not-made-by-hand") accrued to icons that are alleged to have come into existence miraculously, not by a human painter. Such images functioned as powerful relics as well as icons, and their images were naturally seen as especially authoritative as to the true appearance of the subject: naturally and especially because of the reluctance to accept mere human productions as embodying anything of the divine, a commonplace of Christian deprecation of man-made "idols". Like icons believed to be painted directly from the live subject, they therefore acted as important references for other images in the tradition. Beside the developed legend of the mandylion or Image of Edessa, was the tale of the Veil of Veronica, whose very name signifies "true icon" or "true image", the fear of a "false image" remaining strong. A familiar example of an icon of this type within Roman Catholicism is the icon of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the West.

Theology

Christianity teaches that the immaterial God took flesh in the human form of Jesus Christ, making it therefore possible to create depictions of the human form of the Son of God. It is on this basis that the Old Testament proscriptions against making images were overturned for the early Christians by their belief in the Incarnation. Also, the concept of archetype was redefined by the early church fathers in order to better understand that when a person shows veneration toward an image, the intention is rather to honor the person depicted, not the substance of the icon. As St. Basil the Great says, "The honor shown the image passes over to the archetype." He also illustrates the concept by saying, "If I point to a statue of Caesar and ask you 'Who is that?', your answer would properly be, 'It is Caesar.' When you say such you do not mean that the stone itself is Caesar, but rather, the name and honor you ascribe to the statue passes over to the original, the archetype, Caesar himself."[16] So it is with an Icon.

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, only flat panel or bas relief images are used. The Greeks, having a long, pagan tradition of statuary, found the sensual quality of three dimensional representations did more to glorify the human aspect of the flesh rather than the divine nature of the spirit and so prohibitions were created against statuary. The Romans, on the other hand, did not adopt these prohibitions and so there is still statuary among the Roman Catholics to this day. Because the Greeks rejected statuary, the Byzantine style of iconography was developed in which figures were stylized in a manner that emphasized their holiness rather than their humanity. Symbolism allowed the icon to present highly complex material in a very simple way, making it possible to educate even the illiterate in theology. The interiors of Orthodox Churches are often completely covered in icons.

Stylistic developments

Although there are earlier records of their use, no panel icons earlier than the few from the 6th century preserved at the Greek Orthodox Monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai survive.[17] The surviving evidence for the earliest depictions of Christ, Mary and saints therefore comes from wall-paintings, mosaics and some carvings. They are realistic in appearance, in contrast to the later stylization. They are broadly similar in style, though often much superior in quality, to the mummy portraits done in wax (encaustic) and found at Fayyum in Egypt. As we may judge from such items, the first depictions of Jesus were generic rather than portrait images, generally representing him as a beardless young man. It was some time before the earliest examples of the long-haired, bearded face that was later to become standardized as the image of Jesus appeared. When they did begin to appear there was still variation. Augustine of Hippo (354-430)[18] said that no one knew the appearance of Jesus or that of Mary. However, Augustine was not a resident of the Holy Land and therefore was not familiar with the local populations and their oral traditions. Gradually, paintings of Jesus took on characteristics of portrait images.

At this time the manner of depicting Jesus was not yet uniform, and there was some controversy over which of the two most common icons was to be favored. The first or "Semitic" form showed Jesus with short and "frizzy" hair; the second showed a bearded Jesus with hair parted in the middle, the manner in which the god Zeus was depicted. Theodorus Lector remarked[19] that of the two, the one with short and frizzy hair was "more authentic". To support his assertion, he relates a story (excerpted by John of Damascus) that a pagan commissioned to paint an image of Jesus used the "Zeus" form instead of the "Semitic" form, and that as punishment his hands withered.

Though their development was gradual, we can date the full-blown appearance and general ecclesiastical (as opposed to simply popular or local) acceptance of Christian images as venerated and miracle-working objects to the 6th century, when, as Hans Belting writes,[20] "we first hear of the church's use of religious images." "As we reach the second half of the sixth century, we find that images are attracting direct veneration and some of them are credited with the performance of miracles"[21] Cyril Mango writes,[22] "In the post-Justinianic period the icon assumes an ever increasing role in popular devotion, and there is a proliferation of miracle stories connected with icons, some of them rather shocking to our eyes". However, the earlier references by Eusebius and Irenaeus indicate veneration of images and reported miracles associated with them as early as the 2nd century. What might be shocking to our contemporary eyes may not have been viewed as such by the early Christians. Acts 5:15 reports that "people brought the sick into the streets and laid them on beds and mats so that at least Peter's shadow might fall on some of them as he passed by."

Iconoclast period

There was a continuing opposition to misuse of images within Christianity from very early times. "Whenever images threatened to gain undue influence within the church, theologians have sought to strip them of their power".[23] Further,"there is no century between the fourth and the eighth in which there is not some evidence of opposition to images even within the Church.[24] Nonetheless, popular favor for icons guaranteed their continued existence, while no systematic apologia for or against icons, or doctrinal authorization or condemnation of icons yet existed.

The use of icons was seriously challenged by Byzantine Imperial authority in the 8th century. Though by this time opposition to images was strongly entrenched in Judaism and Islam, attribution of the impetus toward an iconoclastic movement in Eastern Orthodoxy to Muslims or Jews "seems to have been highly exaggerated, both by contemporaries and by modern scholars".[25]

Though significant in the history of religious doctrine, the Byzantine controversy over images is not seen as of primary importance in Byzantine history. "Few historians still hold it to have been the greatest issue of the period..."[26]

The Iconoclastic Period began when images were banned by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian sometime between 726 and 730. Under his son Constantine V, a council forbidding image veneration was held at Hieria[27] near Constantinople in 754. Image veneration was later reinstated by the Empress Regent Irene, under whom another council was held reversing the decisions of the previous iconoclast council and taking its title as Seventh Ecumenical Council. The council anathemized all who hold to iconoclasm, i.e. those who held that veneration of images constitutes idolatry. Then the ban was enforced again by Leo V in 815. And finally icon veneration was decisively restored by Empress Regent Theodora.

From then on all Byzantine coins had a religious image or symbol on the reverse, usually an image of Christ for larger denominations, with the head of the Emperor on the obverse, reinforcing the bond of the state and the divine order.[7]

Greek-speaking regions

Today icons are used particularly among Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Coptic and Eastern Catholic Churches.

Of the icon painting tradition that developed in Byzantium, with Constantinople as the chief city, we have only a few icons from the 11th century and none preceding them, in part because of the Iconoclastic reforms during which many were destroyed, and also because of plundering by Venetians in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, and finally the taking of the city by the Islamic Turks in 1453.

It was only in the Comnenian period (1081–1185) that the cult of the icon became widespread in the Byzantine world, partly on account of the dearth of richer materials (such as mosaics, ivory, and enamels), but also because an iconostasis a special screen for icons was introduced then in ecclesiastical practice. The style of the time was severe, hieratic and distant.

In the late Comnenian period this severity softened, and emotion, formerly avoided, entered icon painting. Major monuments for this change include the murals at Daphni (ca. 1100) and Nerezi near Skopje (1164). The Theotokos of Vladimir (ca. 1115, illustration, right) is probably the most representative example of the new trend towards spirituality and emotion.

The tendency toward emotionalism in icons continued in the Paleologan period, which began in 1261. Paleologan art reached its pinnacle in mosaics such as those of the Kariye Camii (the former Chora Monastery). In the last half of the 14th century, Paleologan saints were painted in an exaggerated manner, very slim and in contorted positions, that is, in a style known as the Paleologan Mannerism, of which Ochrid's Annunciation is a superb example.

After 1453, the Byzantine tradition was carried on in regions previously influenced by its religion and culture— in the Balkans and Russia, Georgia in the Caucasus, and, in the Greek-speaking realm, on Crete.

Crete

Crete was under Venetian control from 1204 and became a thriving center of art with eventually a Scuola di San Luca, or organized painter's guild on Western lines. Cretan painting was heavily patronized both by Catholics of Venetian territories and by Eastern Orthodox. For ease of transport, Cretan painters specialized in panel paintings, and developed the ability to work in many styles to fit the taste of various patrons. El Greco, who moved to Venice after establishing his reputation in Crete, is the most famous artist of the school, who continued to use many Byzantine conventions in his works. In 1669 the city of Heraklion, on Crete, which at one time boasted at least 120 painters, finally fell to the Turks, and from that time Greek icon painting went into a decline, with a revival attempted in the 20th century by art reformers such as Photios Kontoglou, who emphasized a return to earlier styles.

Symbolism

In the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, and of the Early Medieval West, very little room is made for artistic license. Almost everything within the image has a symbolic aspect. Christ, the saints, and the angels all have halos. Angels (and often John the Baptist) have wings because they are messengers. Figures have consistent facial appearances, hold attributes personal to them, and use a few conventional poses.

Colour too plays an important role. Gold represents the radiance of Heaven; red, divine life. Blue is the color of human life, white is the uncreated essence of God, only used for resurrection and transfiguration of Christ. If you look at icons of Jesus and Mary: Jesus wears red undergarment with a blue outer garment (God become Human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red overgarment (human was granted gifts by God), thus the doctrine of deification is conveyed by icons. Letters are symbols too. Most icons incorporate some calligraphic text naming the person or event depicted. Even this is often presented in a stylized manner.

In later Western depictions, much of the symbolism survives, though there is far less consistency. Artistic license allows the painter much more freedom over the depiction. Examples of this style abound. And yet, despite the imagination and brilliance of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, it is still quite easy to identify the saint depicted because the traditional attribute and appearance of Peter is still present.

Russia

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be as large as a table top. Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner (see Icon Corner). There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostás) a wall of icons.

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 988 A.D. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by usage, some of which had originated in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians—notably Andrei Rublev and Dionisius—widened the vocabulary of iconic types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere. The personal, improvisatory and creative traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Russia before the 17th century, when Simon Ushakov's painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from Protestant as well as Catholic Europe.

In the mid-17th century, changes in liturgy and practice instituted by Patriarch Nikon resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists, the persecuted "Old Ritualists" or "Old Believers", continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice. From that time icons began to be painted not only in the traditional stylized and nonrealistic mode, but also in a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism, and in a Western European manner very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. The Stroganov movement and the icons from Nevyansk rank among the last important schools of Russian icon-painting.

Western Christianity

Until the 13th century, icons followed a broadly similar pattern in West and East - although very few survive from this early from either tradition. Western icons, which are not usually so termed, were largely patterned on Byzantine works, and equally conventional in composition and depiction. From this point on the western tradition came slowly to allow the artist far more flexibility, and a more realist approach to the figures. If only because there was a much smaller number of skilled artists, the quantity of icons, in the sense of panel paintings, was much smaller in the West, and in most Western settings a single diptych as an altarpiece, or in a domestic room, probably stood in place of the larger collections typical of Orthodox "icon corners".

Only in the 15th century did production of painted icons begin to approach Eastern levels, and in this century the use of icons in the West was enormously increased by the introduction of prints on paper, mostly woodcuts which were produced in vast numbers (although hardly any survive). They were mostly sold, hand-coloured, by churches, and the smallest sizes (often only an inch high) were affordable even by peasants, who glued or pinned them straight onto a wall.

With the Reformation, after an initial uncertainty among early Lutherans, who painted a few "icon"-like depictions of leading Reformers, and continued to paint scenes from Scripture, Protestants came down firmly against icon-like portraits, especially larger ones, even of Christ. Many Protestants found these "idolatrous". Narrative Biblical scenes, especially as book illustrations, remained acceptable, and were encouraged. The Catholics maintained, even intensified the traditional use of icons, both printed and on paper, now using the different styles of the Renaissance and Baroque. Popular Catholic imagery to a certain extent has remained attached to a Baroque style of about 1650, especially in Italy and Spain.

Traditions in other regions

In Romania, icons painted as reversed images behind glass and set in frames were common in the 19th century and are still made. The process know as Reverse painting on glass "In the Transylvanian countryside, the expensive icons on panels imported from Moldavia, Wallachia, and Mt. Athos were gradually replaced by small, locally produced icons on glass, which were much less expensive and thus accessible to the Transylvanian peasants..."[28]

The Egyptian Coptic Church and the Ethiopian Church also have distinctive, living icon painting traditions. Coptic icons have their origin in the Hellenistic art of Egyptian Late Antiquity, as exemplified by the Fayum mummy portraits. Beginning in the 4th century, churches painted their walls and made icons to reflect an authentic expression of their faith.

Protestant Reformation

The abundant use and veneration historically accorded images in the Roman Catholic Church was a point of contention for Protestant reformers, who varied in their attitudes toward images. In the consequent religious struggles many statues were removed from churches, and there was also iconoclasm, or destruction of images, often by force, in all Protestant regions. Notable episodes were in England during the English Reformation, and then more severely in the English Civil War, in Flanders in the Beeldenstorm, and in France during the Wars of Religion.

Though followers of Zwingli and Calvin were more severe in their rejection, Lutherans tended to be moderate: many of their parishes displayed statues and crucifixes. A recent joint Lutheran-Orthodox statement made in the 7th Plenary of the Lutheran-Orthodox Joint Commission,[29] on July 1993 in Helsinki, reaffirmed the Ecumenical Council decisions on the nature of Christ and the veneration of images:

7. As Lutherans and Orthodox we affirm that the teachings of the ecumenical councils are authoritative for our churches. The ecumenical councils maintain the integrity of the teaching of the undivided Church concerning the saving, illuminating/justifying and glorifying acts of God and reject heresies which subvert the saving work of God in Christ. Orthodox and Lutherans, however, have different histories. Lutherans have received the Nicaeno?Constantinopolitan Creed with the addition of the filioque. The Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which rejected iconoclasm and restored the veneration of icons in the churches, was not part of the tradition received by the Reformation. Lutherans, however, rejected the iconoclasm of the 16th century, and affirmed the distinction between adoration due to the Triune God alone and all other forms of veneration (CA 21). Through historical research this council has become better known. Nevertheless it does not have the same significance for Lutherans as it does for the Orthodox. Yet, Lutherans and Orthodox are in agreement that the Second Council of Nicaea confirms the christological teaching of the earlier councils and in setting forth the role of images (icons) in the lives of the faithful reaffirms the reality of the incarnation of the eternal Word of God, when it states: "The more frequently, Christ, Mary, the mother of God, and the saints are seen, the more are those who see them drawn to remember and long for those who serve as models, and to pay these icons the tribute of salutation and respectful veneration. Certainly this is not the full adoration in accordance with our faith, which is properly paid only to the divine nature, but it resembles that given to the figure of the honored and life?giving cross, and also to the holy books of the gospels and to other sacred objects" (Definition of the Second Council of Nicaea).

Contemporary Christianity

Today attitudes can vary even from church to church within a given denomination, whether Catholic or Protestant. Protestants generally use religious art for teaching and for inspiration, but such images are not venerated as in Orthodoxy, and many Protestant church sanctuaries contain no imagery at all.

After the Second Vatican Council declared that the use of statues and pictures in churches should be moderate, most statuary was removed and even destroyed from many Catholic Churches. Eastern Orthodoxy, however, continues to give such strong importance to the use and veneration of icons that they are often seen as the chief symbol of Orthodoxy. Catholicism has a long tradition of valuing the arts and was the prime patron of artists even after the Renaissance. Present-day imagery within Roman Catholicism varies in style from traditional to modern, and is affected by trends in the art world in general.

Icons are often illuminated with a candle or jar of oil with a wick. (Beeswax for candles and olive oil for oil lamps are preferred because they burn very cleanly, although other materials are sometimes used.) The illumination of religious images with lamps or candles is an ancient practice pre-dating Christianity.

Miracles

In the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition there are reports of particular, Wonderworking icons that exude myrrh (fragrant, healing oil), or perform miracles upon petition by believers. When such reports are verified by the Orthodox hierarchy, they are understood as miracles performed by God through the prayers of the saint, rather than being magical properties of the painted wood itself. Theologically, all icons are considered to be sacred, and are miraculous by nature, being a means of spiritual communion between the heavenly and earthly realms. However, it is not uncommon for specific icons to be characterised as "miracle-working", meaning that God has chosen to glorify them by working miracles through them. Such icons are often given particular names (especially those of the Virgin Mary), and even taken from city to city where believers gather to venerate them and pray before them. Islands like that of Tinos are renowned for possessing such "miraculous" icons, and are visited every year by thousands of pilgrims.

Eastern Orthodox and Catholic teaching

Icons are used particularly in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic churches.

The Eastern Orthodox view of the origin of icons is quite different from that of secular scholars and from some in contemporary Roman Catholic circles: "The Orthodox Church maintains and teaches that the sacred image has existed from the beginning of Christianity", Léonid Ouspensky has written.[30] Accounts that some non-Orthodox writers consider legendary are accepted as history within Eastern Orthodoxy, because they are a part of church tradition. Thus accounts such as that of the miraculous "Image Not Made by Hands", and the weeping and moving "Mother of God of the Sign" of Novgorod are accepted as fact: "Church Tradition tells us, for example, of the existence of an Icon of the Savior during His lifetime (the "Icon-Made-Without-Hands") and of Icons of the Most-Holy Theotokos [Mary] immediately after Him."[31] Eastern Orthodoxy further teaches that "a clear understanding of the importance of Icons" was part of the church from its very beginning, and has never changed, although explanations of their importance may have developed over time. This is due to the fact that iconography is rooted in the theology of the Incarnation (Christ being the eikon of God) which didn't change, though its subsequent clarification within the Church occurred over the period of the first seven Ecumenical Councils. Also, icons served as tools of edification for the illiterate faithful during most of the history of Christendom.

Eastern Orthodox find the first instance of an image or icon in the Bible when God made man in His own image (Septuagint Greek eikona), in Genesis 1:26-27. In Exodus, God commanded that the Israelites not make any graven image; but soon afterwards, he commanded that they make graven images of cherubim and other like things, both as statues and woven on tapestries. Later, Solomon included still more such imagery when he built the first temple. Eastern Orthodox believe these qualify as icons, in that they were visible images depicting heavenly beings and, in the case of the cherubim, used to indirectly indicate God's presence above the Ark.

In the Book of Numbers it is written that God told Moses to make a bronze serpent, Nehushtan, and hold it up, so that anyone looking at the snake would be healed of their snakebites. In John 3, Jesus refers to the same serpent, saying that he must be lifted up in the same way that the serpent was. John of Damascus also regarded the brazen serpent as an icon. Further, Jesus Christ himself is called the "image of the invisible God" in Colossians 1:15, and is therefore in one sense an icon. As people are also made in God's images, people are also considered to be living icons, and are therefore "censed" along with painted icons during Orthodox prayer services.

According to John of Damascus, anyone who tries to destroy icons "is the enemy of Christ, the Holy Mother of God and the saints, and is the defender of the Devil and his demons." This is because the theology behind icons is closely tied to the Incarnational theology of the humanity and divinity of Jesus, so that attacks on icons typically have the effect of undermining or attacking the Incarnation of Jesus himself as elucidated in the Ecumenical Councils.

The Eastern Orthodox teaching regarding veneration of icons is that the praise and veneration shown to the icon passes over to the archetype (Basil of Caesarea,On the Holy Spirit 18:45: "The honor paid to the image passes to the prototype"). Thus to kiss an icon of Christ, in the Eastern Orthodox view, is to show love towards Christ Jesus himself, not mere wood and paint making up the physical substance of the icon. Worship of the icon as somehow entirely separate from its prototype is expressly forbidden by the Seventh Ecumenical Council; standard teaching in the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches alike conforms to this principle. The Catholic Church accepts the same Councils and the canons therein which codified the teaching of icon veneration.

The Latin Church of the West, which after 1054 was to become known separately as the Roman Catholic Church, accepted the decrees of the iconodule Seventh Ecumenical Council regarding images. There is some minor difference, however, in the Catholic attitude to images from that of the Orthodox. Following Gregory the Great, Catholics emphasize the role of images as the Biblia Pauperum, the "Bible of the Poor," from which those who could not read could nonetheless learn. This view of images as educational is shared by most Protestants.

Catholics also, however, accept in principle the Eastern Orthodox veneration of images, believing that whenever approached, sacred images are to be reverenced. Though using both flat wooden panel and stretched canvas paintings, Catholics traditionally have also favored images in the form of three-dimensional statuary, whereas in the East statuary is much less widely employed.

Septuagint

The Greek word eikon means an image or likeness of any kind. Anything that represents something else is an eikon. Nothing is implied about sanctity or its absence, or veneration or its absence by the word itself.

The Septuagint is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures used by the early Christians, and Eastern Orthodox consider it the only authoritative text of those Scriptures. In it the word eikon is used for everything from man being made in the divine image to the "molten idol" placed by Manasses in the Temple.

- Genesis 1:26-27;

- Genesis 5:1-3;

- Genesis 9:6;

- Deuteronomy 4:16

- 1 Samuel (1 Kings) 6:11 (Alexandrian manuscript);

- 2 Kings 11:18;

- 2 Chronicles 33:7;

- Psalm 38:7

- Psalm 72:20;

- Isaiah 40, 19-20;

- Ezekiel 7:20;

- Ezekiel 8:5 (Alexandrian manuscript);

- Ezekiel 16:17;

Ezekiel 23:14; Daniel 2:31,32,34,35; Daniel 3:1,2,3,5,7,11,12,14,15,18; Hosea 13:2

Be aware that Septuagint numberings and names and the English Bible numberings and names are not uniformly identical.

New Testament

In the New Testament the term is used for everything from Jesus as the image of the invisible God (Colossians 1:15) to the image of Caesar on a Roman coin (Matthew 22:20) to the image of the Beast in the Apocalypse (Revelation 14:19). Here is a complete listing:

- Matthew 22:20;

- Mark 12:16

- Luke 20:24

- Romans 1:23

- Romans 8:29;

- 1 Corinthians 11:7;

- 1 Corinthians 15:49

- 2 Corinthians 3:18;

- 2 Corinthians 4:4;

- Colossians 1:15;

- Colossians 3:10;

- Hebrews 10:1;

- Revelation 13:14;

- Revelation 13:15;

- Revelation 14:9;

- Revelation 14:11

- Revelation 15:2

- Revelation 16:2

- Revelation 19:20;

- Revelation 20:4.

Other religious traditions

Other religious traditions, such as Hinduism, have a very rich iconography called murti, while others, such as Islam, severely limit the use of visual representations (see Islamic art). Yet even though Hinduism is commonly represented by such anthropomorphic religious murtis, aniconism is equally represented with such abstract symbols of God such as the Shiva linga and the saligrama.[32] Moreover, Hindus have found it easier to focus on anthropmorphic icons, because Lord Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 12, Verse 5, that it is much more difficult to focus on God as the unmanifested than God with form, due to human beings having the need to perceive via the senses.[33]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ The Meaning of Icons, by Vladimir Lossky with Léonid Ouspensky, SVS Press, 1999. (ISBN 0-913836-99-0)

- ↑ Rev. Dr. Steven Bingham, Early Christian Attitudes Toward Images, Orthodox Research Institute, 2004

- ↑ Veronica and her Cloth, Kuryluk, Ewa, Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, 1991

- ↑ John Francis Wilson Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the Lost City of Pan I.B. Tauris, London, 2004.

- ↑ Fox, Pagans and Christians, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1989).

- ↑ Dom Gregory Dix, The Shape of the Liturgy (New York: Seabury Press, 1945) 413-414.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Robin Cormack, "Writing in Gold, Byzantine Society and its Icons", 1985, George Philip, London, ISBN 054001085-5

- ↑ Excerpted by Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos; this passage is by some considered a later interpolation.

- ↑ AvellinoMagazine.it

- ↑ Mariadinazareth.it

- ↑ STblogs.org

- ↑ Margherita Guarducci, The Primacy of the Church of Rome, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991) 93-101.

- ↑ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p111, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0719539714

- ↑ Father H. Hosten in his book Antiquities notes the following "The picture at the mount is one of the oldest, and, therefore, one of the most venerable Christian paintings to be had in India."

- ↑ Cormack, Robin (1997). Painting the Soul; Icons, Death Masks and Shrouds. Reaktion Books, London. p. 46.

- ↑ Alan Brent, The imperial cult and the development of church order: concepts and images of authority in paganism and early Christianity before the Age of Cyprian, illustrated, Brill, 1999, pp. 204-5, paraphrasing St. Basil, Homily 24: "on seeing an image of the king in the square, one does not allege that there are two kings". Veneration of the image venerates its original: a similar analogy is implicit in the images used for the Roman Imperial cult. It does not occur in the Gospels.

- ↑ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 853312702

- ↑ De Trinitatis 8:4-5.

- ↑ Church History 1:15.

- ↑ Belting, Likeness and Presence, University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- ↑ Patricia Karlin-Hayter, The Oxford History of Byzantium, Oxford, 2002.

- ↑ Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453, University of Toronto Press, 1986.

- ↑ Belting, Likeness and Presence, Chicago and London, 1994.

- ↑ Ernst Kitzinger, The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm, Dumbarton Oaks, 1954, quoted by Pelikan, Jaroslav; The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600-1700, University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- ↑ Pelikan, The Spirit of Eastern Christendom

- ↑ Patricia Karlin-Hayter, Oxford History of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ↑ See Council of Hieria.

- ↑ Dancu, Juliana and Dumitru Dancu, Romanian Icons on Glass, Wayne State University Press, 1982.

- ↑ Helsinki.fi

- ↑ Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon", St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1978.

- ↑ These Truths We Hold, St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, 1986.

- ↑ Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, by Jeanne Fowler, pgs. 42-43, at Books.Google.com and Flipside of Hindu symbolism, by M. K. V. Narayan at pgs. 84-85 at Books.Google.com

- ↑ http://www.bhagavad-gita.org/Gita/verse-12-04.html

External links

Orthodox

- Iconography Guide -free eLearning site

- Orthodox Iconography by Elias Damianakis

- The Iconic and Symbolic in Orthodox Iconography

- On the difference of Western Religious Art and Orthodox Iconography

- A Discourse in Iconography by St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco

- Church of the Nativity - Explanation of Orthodox Christian Icons

- Concerning the Veneration of Icons

- Holy Icons: Theology in Color (Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese)

Catholic

- "Veneration of Images" article from The Catholic Encyclopedia

Pictures

- Icons of Mount Athos

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America: Icons

- Gallery of icons, murals and mosaics (mostly Russian) from 11th to 20th century

- www.eikonografos.com A huge collection of Byzantine Icons

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||